On Tuesday February 14th 1984, Zetra Olympic Hall in Sarajevo was the setting of Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean’s monumental Olympic triumph cheered on by 8500 spectators in the hall, and millions across the globe. The ultramodern, copper-roofed complex, designed by architects Lidumil Alikalfic and Dušan Đapa was officially opened by then President of the International Olympic Committee, Juan Antonio Samaranch on February 14th 1982 (exactly 2 years before Jayne and Chris’ stunning 6.0 Bolero).

Following the Olympics, Zetra was the setting of further record breaking, while hosting a number of international Speed Skating contests, until 1991 as well as the last Olympic closing ceremony held in an indoor venue until Vancouver 2010. That same year (July 28th 1991), some 30,000 youngsters packed the hall out (with a further 50,000) outside, celebrating peace and hundreds of thousands protested on the streets against a war few believed would come so soon, causing more than ten thousand deaths.

Yet less than a year later on April 6th 1992, come it did. And on May 21st (according to Alikalfic) or May 25th (Wikipedia & William Oscar Johnson’s ‘The Killing Ground’) Serbian forces under the command of General Ratko Mladić caused substantial damage to Zetra through shelling, bombing and fire, as well as destroying the building’s blueprints forever. Such was the wreckage, that the following year, with ever decreasing resources and an ever increasing death toll, Zetra’s wooden seating was being taken away daily to be fashioned into much needed coffins, many being buried in a cemetery set up at the rear of the Arena after being placed in the venue’s basement which had become a makeshift morgue.

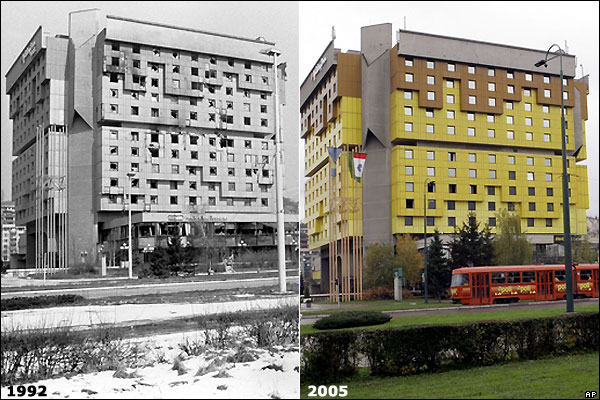

The Olympic committee’s residence 8 years before (the freshly opened distinctive yellow Holiday inn) envisioned by celebrated Bosnian architect Ivan Straus, as an ‘indoor city’ became ground zero, located on what became known as ‘Sniper’s Alley’. From 1992-1995 it housed war reporters from around the world, filing report after report where, as BBC Correspondent Martin Bell stated “you didn’t go out to the war, the war came in to you.” The hotel which was hit in excess of a hundred times in the course of the three year siege (the lengthiest siege to hit any capital city in modern conflict) has since be re-named the Olympic Hotel Holiday Sarajevo in recognition of its original construction and is once again an important symbol of the architecture and history of Sarajevo.

On December 14th 1995, with the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement the war finally came to an end. A war which had left so many dead and so much of the Sarajevo Olympics’ legacy in tatters. A year later The Stabilisation Force in Bosnia and Herzegovina (SFOR), a NATO-led multinational peacekeeping force was deployed primarily to “deter hostilities and stabilise the peace”. In December 1997 the SFOR set about reconstructing Zetra, a $32m project made possible by a $11.5m donation from the International Olympic Committee. Three years later the project was completed and the Hall (renamed as The Juan Antonio Samaranch Olympic Hall following his death in 2010), is once again in use as a sporting arena and houses a small museum commemorating the 1984 Olympics. In 2014, Chris (along with Jayne) returned to perform once again at the arena marking 30 years since “That day changed our lives forever and will always be in our hearts and our memories, not just for that day but for the life it gave us.” In 2019 the hall was a venue for the European Youth Olympic Winter Festival Ice Hockey, with figure skating taking place at the nearby Skenderija Hall. While, Tripadvisor reviews make clear that The Juan Antonio Samaranch Olympic Hall is today less the glorious mecca ice dance fanatics may foresee, and more a municipal concrete carbuncle, its history both splendid and dreadful, make it a place worthy of remembrance.

1984 winners of the Ice Dance Gold Medal Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean made history at Zetra with their run of 6.0s

Following The Bosnian War, Zetra lay in ruins, it’s seats having been ripped out for coffins, it’s basement used as a morgue and out lands became a cemetery

By the time war ceased thousands had lost their lives

Following the war, with vital assistance from the International Olympic City the arena was restored ensuring a venue which had played such a big part in both Olympic and Bosnian history was not lost forever.

One thought on “From Golden Glory to Hellish Horrors”